Make your customers your biggest fans

Make your customers your biggest fans

We are trusted by these well known brands

Provide your leaders, managers and frontline staff with the tools they need to measure and deliver an outstanding customer experience.

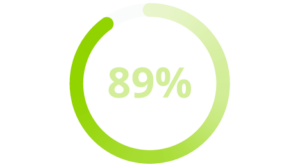

89% of companies see customer experience as a key factor in driving customer loyalty and retention.

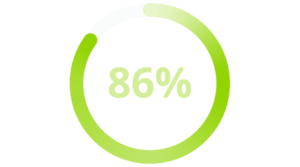

86% of buyers are willing to pay more for a great customer experience.

We get it. Your customers are your business.

Our Customer Experience solutions can help you to create an organisation-wide strategy to address and utilise customer feedback, empower team autonomy and build the foundations of a customer-centric culture.

From basic customer service to customer recovery, our Customer Experience solutions can also guide your whole team in optimising the customer journey.

Our products

Customer feedback is the secret weapon for improving CX. We can help you to access actionable insights from every customer demographic. To drive your CX – and your business – forward.

Our range of survey sharing methods mean you can engage with your customers via the channel that suits them best – whether that’s IVR, SMS, Email, Web, Webchat, Mobile Apps or In-Store. Get the feedback you need to deliver the best experience for your customers.

Our fully customisable CX analytics dashboard includes KPI tracking capabilities and dedicated views for customer responses and trends, helping you to track and analyse your CX journey as it happens.

Give your team the power to turn insights into results by providing transparent access to customer feedback relevant to them. They can only improve performance if they know what customers think.

With social media acting as a global soapbox, it can be as much of a blight as a boon to businesses. Only with real-time customer conversation and brand mention tracking do you have the power to engage happy customers – and appease dissatisfied ones.

Our Social Media Tracker can help you to provide impeccable customer service and experience, and track and act on customer conversations. As well as other mentions of your brand.

Speech & text analytics can do a lot for your business. Allowing you to automate quality assurance, increase revenues, reduce operational cost, improve customer experiences, and identify potential fraudulent claims in real-time.

All the tools you need under one roof

Meet Bedrock – Our customer experience platform

Customer experience can make or break your business. To remain competitive you must deliver the best customer experience within your power.

To do that, you need to know exactly what your customers think and feel about your brand. This is where our Customer Experience solutions can help.

Challenges we can help you crack

If you’re looking for a solution but not too sure where to start, here are some examples of particular challenges our CX technology can help you overcome – and fast.

Our solutions

Solutions to support specific businesses and specific roles

If you’re not sure where to start, but are looking to make positive changes within a certain business or department, then we’ve got you covered.

With CX solutions tailored to:

Calling all Insight Managers: Do your reports matter?

The way you share results of your insight programmes can make all the difference, so how you interpret these outcomes and turn them into actions that matter is important. But before you begin collating data for your report, there are a few things to consider.

How data-driven marketing can positively impact your CX strategy

Customer experience (CX) is not just a buzzword, but a critical competitive differentiator. It’s the golden thread that weaves through every customer interaction, shaping perceptions, influencing decisions, and fostering loyalty. As such, a stellar CX is no longer a nice-to-have, but a must-have.

Solicited or unsolicited customer feedback: Which is more valuable for your business?

There is a myriad of ways in which companies request feedback from their customers – focus groups, customer panels, CSAT or NPS surveys and customer interviews. In all of these it is the business that is initiating the process and so these are examples of solicited feedback.

Wake-up call: The consequences of ignoring customer feedback

In today’s cutthroat world of business, staying attuned to the voice of your customers is more important than ever. Ignoring their feedback could spell disaster for your enterprise, potentially leading to dwindling sales and shrinking profits. While the saying, “the customer is always right,” may not hold true in every situation, it is essential to pay heed to their opinions and take their feedback into account.

Fill in your details via the button below and we'll be in touch.